|

Language

Overview

Despite of some resemblance and intermingling, The Georgians, ethnically and linguistically, are unrelated to the Indo-Europeans (Russians, Armenians, or any Western European groups). They form a group of their own, named "Ibero-Caucasian", "South Caucasian" or "Kartvelian" (the latter is the Georgians' own name for their nation). Professor Nikolai Marr, a prominent scholar of the Caucasian languages, brought into use the term "Japhetic" to designate a group (which includes Georgian) which he and other scholars believed to have inhabited the Mediterranean basin before the arrival of the Indo-Europeans circa II millenium BCE. These scholars believe that of this group of people, known as "Proto-Iberians", the Georgians and the Basques (in Spain) are the sole survivors, though the extinct Etruscans in Italy may have belonged to a kindred family. Certain affinities between the Basque and Georgian languages, as well as resemblances in popular customs, traditions and legends have been (and still are ) used to highlight their probable affinity.

The Georgian language belongs to the Paleocaucasian Ethnolinguistic Family, the representative people of which are the direct descendents of the oldest population of Caucasus. This Family is divided into three branches:

1) Western Caucasian, or Abkhaz-Adighian - unifies modern Abkhazians, Abazians, Adighians, Cherkezians and Kabardians;

2) Eastern Caucasian, or Chechen-Dagestanian - Chechenians, Ingushs and Dagestanians (Avarians, Lezgians, Darguelians, Laks and etc.);

3) Southern, or Kartvelian- represented by Georgian people, which consist of three main subethnical groups - Karts, Zans or Mengrel-Chans and Svans. Division of the previous Kartvelian language into Georgian, Zanian and Svanian branches begins in the III-II mill. B.C.

The Georgian language is the state language of Georgia. Georgian is the only language in the Ibero-Caucasian family that has its own ancient script. The most ancient writings date back to the 5th century AD, though recent findings suggest earlier existence of the literary language. The Georgian script is a unique writing system, conveying the sound composition of the Georgian speech and forming the written and printed symbols of the national Georgian language.

The development of the Georgian alphabet can be broken into three stages: Asomtavruli (unknown dates), Nuskha-Khutsuri (from the 9th century, still used by the Georgians Orthodox Church), and Mkhedruli (contemporary Georgian script, from the 11th century).

Both the ancient and modern alphabets are extremely simple, precious and economic. Each sound has its corresponding symbol and vice versa. Nowadays, the Georgian alphabet includes 33 symbols (5 vowels and 28 consonants). The shape of the letters is unique but their arrangement suggests influence from Indo-European languages.

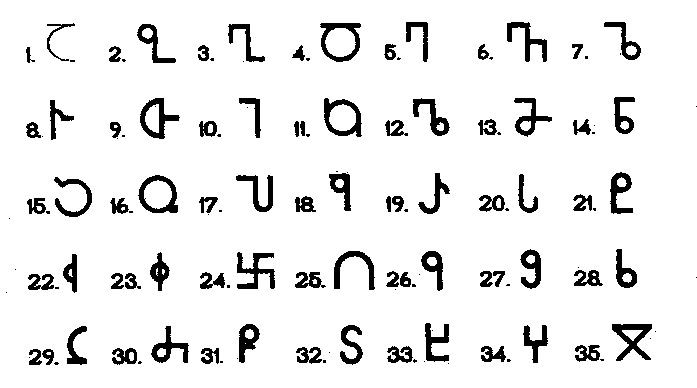

Asomtavruli Script

Asomtavruli is the oldest Georgian script, believed by some

Georgian scholars to be derived from Sumerian alphabet (although their no conclusive proof for this). The script is unique in its shape and symbolism.

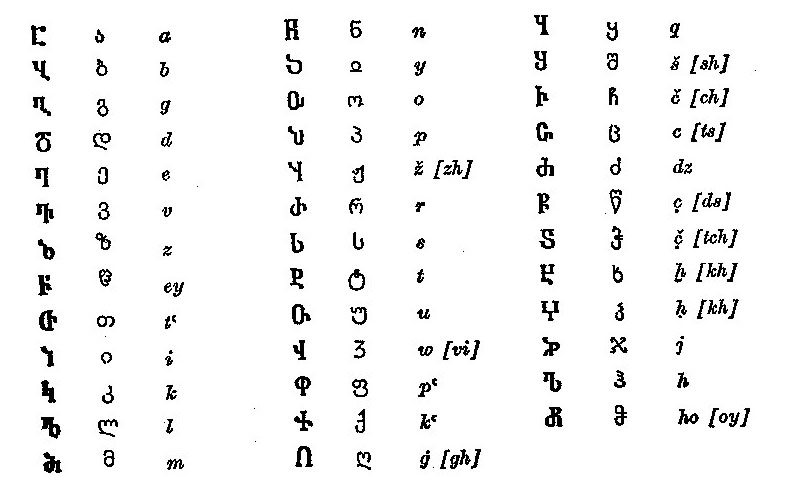

The Georgian alphabet showing: First column, the Ecclestical

(Khutsuri) script; Second column, the Mkhedruli or modern alphabet; Third column the phonetic values

Language and

Nationalism

Language remains one of the key elements in the Georgian identity and a fundamental instrument in forging a nation. Its importance became evident in the late 19th century when the Russian imperial policies endangered its status within the Georgian lands. The rise of the national-liberation movement was in part triggered by the desire to save and revive the Georgian language. Thus, Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli and other prominent members of this movement sought to safeguard the language and adopted a special motto ‘mamuli, ena, sartsmunoeba’ for their program of national awakening in which the language (ena) became one of the three pillars of the national movement. Language also became a subject of bitter dispute between conservative and progressive elements in Georgian society as the Mtkvardaleulni and Tergdaleulni groups discussed the language reform; the latter called for a language reform, which incensed the conservatives, and employed vernacular language in their publications in order to make them more accessible to the common people. The Society for Advancement of Literacy Among the Georgians played an important role in spreading literacy to the masses and Jacob Gogebashvili’s Dedaena served as an important textbook in this process.

During the Soviet era, the Communist authorities made several attempts to abolish the Georgian language as the state language in Georgia, which led to massive protests and revitalized Georgian nationalist sentiments. Georgian dissidents, especially Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava, campaigned under the slogan “ena, mamuli, sartsmunoeba” (language, fatherland, faith) that placed major emphasis on the Georgian language as a rallying point for the Georgian nationalism. In April 1978, the power of Georgian nationalism was revealed when thousands of Georgians took to the streets to protest the Soviet government’s decision to remove Georgian as the official state language of the republic. Facing escalating demands, the government decided against removing the disputed clause and effectively acknowledged its defeat. Currently, Article 8 of the Constitution declares Georgian as the state language of Georgia and the Georgian and Abkhaz languages on the territory of Abkhazia.

Discussions on the place and importance of the language in Georgian history often led to deviations. In 1920s, the Georgian language was studied by Nikolay Marr and his disciples, who founded the Japhetic theory in linguistics. The theory claimed that Japhetic languages, Georgian among them, had existed across Europe before the advent of the Indo-European languages and could be recognized as a foundation over which the Indo-European languages had imposed themselves. Using this model, Marr attempted to apply the Marxist theory of class struggle to linguistics, arguing that these different strata of language corresponded to different social classes. In 1924, he went even further and proclaimed that all the languages of the world descend from a single proto-language which had consisted of four enigmatic elements sal, ber, yon, rosh.

Another important discussion stems from the 10th century scholar Ioane Zosime’s hymn Kebai da didebai kartulisa enisa (Praise and Glorification of the Georgian Language) that glorifies the Georgian language and its unique mission. Ioane Zosime preached, “Buried is the Georgian language as a martyr until the day of the Messiah’s second coming, so that God may look at every language through this language. And so the language is sleeping to this day. And in the Gospels this language is called Lazarus… And friendship it spoke because every secret is buried in this language and dead for four days. Therefore David the Prophet spoke, saying: ‘A thousand years is like one day.’ And within the Georgian Gospels, in Matthew, sits a part, which is a letter, and it will say to all the four thousand secrets. And such are the four days and the man who was dead for four days, for this [it is] buried with him through the death of its baptism. And this language, beautified and blessed by the name of the Lord, humble and afflicted, awaits the day of the second coming of the Lord…”

This hymn spawned messianic tendencies in Georgia of the 1980s and 1990s. Many Georgian dissidents, especially Zviad Gamsakhurdia, explained the hymn in a strictly messianic context, turning it into a major element of nationalist ideology. It was argued that Ioane Zosime’s reference to the Georgian language as Lazarus and his four-day burial referred to the eclipsing of a Japhetic civilization, of which proto-Georgian culture was part, by Indo-European newcomers and the soon-to-be expected revival of Georgia. Furthermore, Gamsakhurdia and his supporters went so far as to claim that at the Judgement Day, the Georgian language, and nation, will take the position of universal spiritual leader and judge of the mankind. Such sentiments, although on the decline, still remain widespread in Georgia and sustain Georgian beliefs of superiority and unique spiritual mission of their language. In recent years, scholars, nationalists and populist politicians often campaign against the influx of Western, particularly American, pop culture and the perceived decline of the Georgian language through numerous English loan-words. The younger generation is especially susceptible to adopting foreign words in the vernacular language.

First Printed

Georgian Books

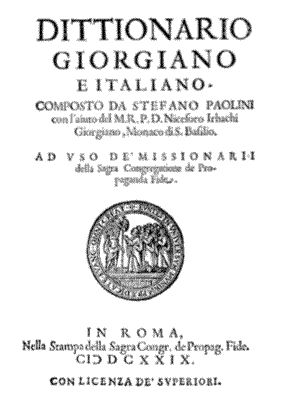

The Catholic and Georgian missionaries in Rome (Italy) helped introduce printed books to the Georgian rulers by the early 17th century. The newly established Catholic Theatine and Capuchin missions also required manuals of the Georgian language and devotional texts for their operations. So, when, in 1626, King Teimuraz I of Kartli-Kakheti sent Nicephorus Irbach (Irubakidze-Cholokashvili) on a diplomatic mission to Rome, the Georgian envoy was enlisted to help solve these problems. During his stay at the Vatican, Nicephorus collaborated with Catholic scholars to produce an extensive Georgian-Italian vocabulary, as well as a brief collection of prayers in colloquial Georgian.

The dictionary, the first Georgian book to be printed, was printed in 1629 and contained over 3,000 words printed in large, clear type of the Mkhedruli alphabet. In 1670, Maggio’s textbook on Georgian grammar appeared in Rome as well. Other religious texts soon followed and, despite their many inaccuracies in light of the limited knowledge of Georgian in Europe, these publications played an important role in the development of Georgian printed culture. In late 17th century, King Archil emigrated to Russia, where he established a vibrant Georgian community at Vsesviatskoe near Moscow and turned his efforts to establishing printing presses that produced Georgians books.

By the late 17th and early 18th century, the number of Georgian books in print had increased but all of them were produced in Moscow or Rome and difficulties of transportation and distribution prevented their circulation within Georgia. The decision to establish a permanent printing press in Tbilisi belonged to King Vakhtang VI (r. 1704-1723), whose reign proved to be a period of constructive activity in almost every sphere. With the help of the prominent Georgian cleric Anthim the Iberian, archbishop of Wallachia (present-day Romania), King Vakhtang set about installing a printing plant in Tbilisi. Archbishop Anthim was himself a master printer and engraver of the first order and pioneer in Rumanian printing, and he sent one of his ablest disciples, the master printer Mihaî Isvanovicî, known in Georgia as Mikheil Stepaneshvili, to open the first Georgian press in Tbilisi.

A page from the book published at the Tbilisi press by Mihaî Isvanovicî

Opened in 1709, the press operated for the next 14 years producing mainly religious texts. One of its greatest achievements was the first print version of Shota Rustaveli's Vepkhistkaosani published in 1712. Before its destruction at the hands of the Ottomans in 1723, the press produced the following titles: Four Cospels in Georgian, 1709; Psalms of David, 1709 (2nd edition 1711; 3rd edition, 1712; 4th edition 1716); Book of Liturgies, 1710; Prayer-Book, 1710 (2nd edition 1717) Book of Hours, 1710 (2nd edition 1717; 3rd edition 1722); Germanos the Monk, Manual on How the Teacher Should Instruct His Pupil, 1711; Shota Rustaveli's Vepkhistkaosani, 1712; Missal (translated from the Greek) 1713; Book of Church Ritual, 1719-1720; Paraklitoni (a liturgical book of the Georgian orthodox Church), 1720; The Book of the Knowledge of Creation (a Persian astronomical treatise, translated by King Vakhtang VI and other scholars), 1721; books of the Bible, including the Prophets and the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, 1709-1722

|